Like most people, the first time I met Terry Wilsey, I found him irksome and crude. He talked and walked funny, he asked strange questions apropros of nothing, he was unkempt and disorganized, he was obsessed with all things G-A-Y in a way that felt a bit cartoonish. Were it not for the natural affinity his partner, Dr. Walter Herron, felt for my then-boyfriend (and then-aspiring physician), Jim Richter, I doubt I would have thought much about either of them again. It was 1997 and I was a young, shallow striver; after a rough, awkward adolescence in which I was seen as a perpetual loser with no friends and nobody looking at me twice as a romantic or sexual prospect, I was enjoying in my 20s the experience of being befriended and often hit on by the handsome, wealthy and powerful so-called “A” Gays of Vegas. It was intoxicating.

Terry and Walt furthered none of those objectives. For that reason alone, they would become the two most important, influential LGBTQ people I would ever know. Now, both of them are dead — Walt was 90 when he died in 2015 after a long decline that savaged his brilliant brain; Terry, at 76 and seemingly in good health, tripped on Dec. 19 while walking his dog, hit his head and never recovered consciousness — and I am a paunchy middle-aged, married father of a 1-year-old. These days I strive not for popularity or prominence but to each day embody the lessons of decency and generosity they taught me so I may teach them to our son.

Back when Jim and I met them, Walt, then in his mid-70s, was a recently retired doctor with a grouchy streak who found gay high society off-putting and superficial for the same reasons he chose a career in public health rather than trying to make the big money in medicine. Terry, while some 25 years younger, often seemed as old in spirit as Walt and equally frustrated by the modern world. To his final weeks, Terry continued to hawk vacation packages and left those sun-yellow business cards on every surface he passed even though the travel agency industry had long since imploded in the face of that darned newfangled do-it-yourself online model.

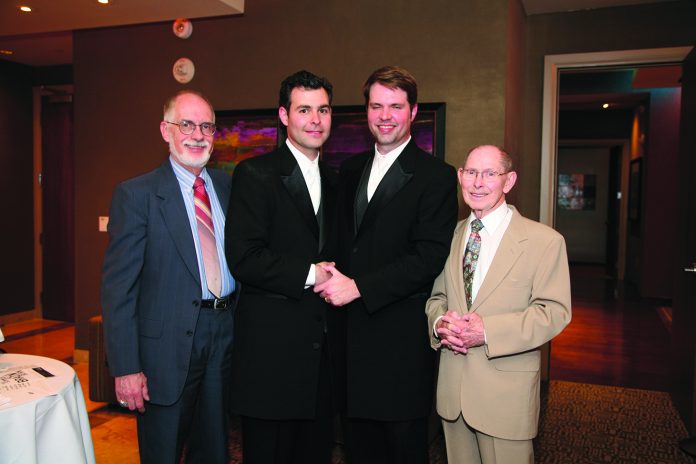

The speed with which Walt and Terry became fixtures in our world was such that I can’t say how or when it happened. We met because Jim started an LGBTQ book club at the Borders on West Sahara that they attended; Terry never read the books but went anyway because if something had “gay” in the name, he was there. Also, he was happy to find something intellectually stimulating that Walt, a voracious reader, would leave the house for. Jim began visiting Walt, who regaled him with tales of a medical career that spanned treating STDs during the Korean War to being fired for coming out as gay as the public health director in Tacoma, Washington, to caring for countless people with AIDS as a staff physician at the VA in Las Vegas in the era when many doctors wouldn’t touch them. Jim, who enrolled in medical school at University of Nevada in 2000, could hardly have found a more admirable, appropriate or relatable mentor.

Soon, we both were over at their weird upside-down East Side house – the kitchen and living room were on the second floor, the bedrooms on the first — multiple times a week. They took care of our poodle when we went away. We took them out for brunch or accompanied them to doctor visits regularly. If we had more visitors than our tiny one-bedroom on South Nellis could manage, we could always send the extra bodies to bunk at Walt and Terry’s.

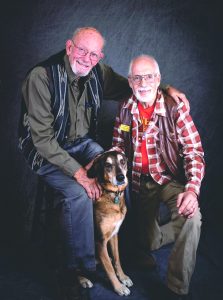

Both Jim and I were multiple time zones from our families, each of which featured revered elders we felt guilty being away from in their crucial declining years. Walt and Terry weren’t our substitute grandparents – though I did dub them our fairy godparents — but we definitely were their adopted grandsons and the experience of doting on one another nourished something in us. In an LGBTQ social world so status-driven and persistently oversexualized, Walt and Terry were a model of an enduring gay couple – together some 40 years when Walt died in 2015 – who were uninterested in money, fashion or popularity and never once made a crude or suggestive remark to or about us.

years of being in a committed relationship.

Neither Walt nor Terry were easy people to get to know or like because, frankly, they didn’t care what you thought of them. They were genuinely themselves, refusing to put on any airs or indulge anyone’s ego, comfortable bickering and squabbling in front of anyone and sometimes being so blunt with strangers – the waiter, the usher, Steve Wynn, whomever – that you wanted to disappear. After my breakup with Jim, for example, I briefly dated one of the country’s most prominent food journalists, who came to Vegas to see me for a weekend. Over dinner, Terry had a burning question: “What do you hear about the curly-q French fries?” We thought he was joking, except that Terry was so guileless and earnest he didn’t tell jokes. “No, really,” he persisted, unaware of our bemusement, “I understand they’ve become very trendy.”

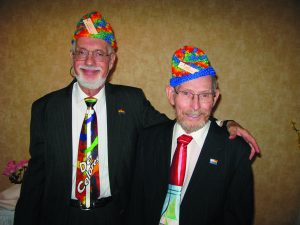

This often made for great fodder for my Las Vegas Weekly column. With “The Olds” – as I dubbed my version of the classic Muppet grumps Statler and Waldorf — I leaned into their queer eccentricity and lack of filter and deliberately placed them in awkward or potentially fraught situations. I took them to show, hotel and restaurant openings and encouraged them to render withering, middling or glowing verdicts within earshot of moguls, chefs and performers. The greatest of these moments came at one of the resort openings at Lake Las Vegas. At breakfast, Terry and Walt complained loudly – and accurately – about the cold food, the gross coffee and the lousy service while also picking apart the chintzy décor. What he didn’t realize was that the table next to ours was populated by a hotel publicist and a group of writers from major travel magazines and websites who were in town to review the joint. The desperate and embarrassed look on the face of the publicist, who I didn’t much like anyway, was brilliant.

The thing about Terry was that if you listened closely and worked through all of his extraneous, random chatter – no small feat – he was thoughtful, curious and often asked questions or made comments that led me, as a journalist, to some terrific stories. The best of these was about Terry’s father, an anesthesiologist who was on hand as an army doctor at the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp. Most of what I heard about David Wilsey over the years were stories of what an abusive and nasty man he had been, and in that narrative his experience in World War II helped explain his anger and cruelty. But a few years ago, he and his sisters unearthed a trove of daily letters Dr. Wilsey wrote to his wife from Europe in that period, elegant and emotional pages that documented the history unfolding around him. Suddenly, this monster was a real person, a man who was once kind and emotive, a remarkably fine writer and keen observer who – at least then – was a romantic husband and doting father. That he became something else to Terry and his sisters only made the material more precious and fascinating, and I got to share them with the world in a major article for The New Republic.

Because my husband, Miles, and I moved away from Vegas in 2011, I never met Terry’s post-Walt partner, Wally, who also died earlier 2020. But Terry and I chatted on video regularly so he could see our son, Nevada, and I could see plainly he was happy. This made me worry about him much less. Terry had selflessly spent a decade caring for Walt when dementia made it increasingly difficult and thankless; I couldn’t imagine that there would be anyone else after Walt who would hack through the miasma of annoying nasal barking that Terry emitted and love him for the kind, well-meaning, industrious, devoted and loyal man he was. Wally did, and how empowering and encouraging is that? There is somebody for everyone after all, and evidently two for Terry Wilsey. Good for him.

Walt’s death was expected, even overdue. Wally’s, too, wasn’t a big surprise given his health conditions. But Terry’s is shocking, disorienting, abrupt and unfair. He was an assiduously healthy eater, trim from always being on the go, from doing yoga and, perhaps, from constantly drinking coffee. He was in good enough shape – and so civic-minded to the end – that he participated in Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine trials. His death robs him of witnessing the cure he helped create as well as the satisfaction of watching Donald Trump, whom he despised, leave the White House. (During the Bush era, he wore his gay flag lapel pin upside down in protest and had such glee and satisfaction when, upon Obama’s inauguration, he got to turn it right-side up.)

Terry’s death is a genuine loss for an LGBTQ community in Vegas that often didn’t appreciate or know what to do with him. He loved being involved, in helping out, as happy to hand out programs or set up tables as to line up and introduce speakers for the monthly Lambda Business Association luncheons. He’d go anywhere, do anything, give any amount that he could afford to support the cause and never sought out recognition for any of it. He was just glad to help.

But this is also acutely personal for me. In all his messiness and strangeness, he taught me to appreciate the diamonds in the rough of humanity. Terry was like a really demanding 19th century English novel; you’re forgiven for finding him too dense, for confusing challenging with boring and giving up. I stuck with it, maddening though he sometimes was. And in doing so, I knew the great privilege of having as true a friend as could exist.

You may think, “Gosh, you’re awfully critical of your so-called friend – and in his obituary of all things!” Yet that’s the thing about Terry. He knew his flaws, perceived or real. This essay would absolutely delight him because it’s true. It’s real. It’s honest. And all of that is why I loved him so much.